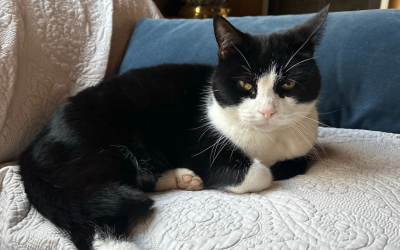

Keep Your Pets Away from Wildlife: Protecting Your Pets During the Avian Flu Outbreak

February 24, 2025 – Recent increases in avian influenza (bird flu) cases across the United States have raised concerns about the risk to both domestic and wild animals. While much […]

Read More